|

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (Review)

Kit Bowen

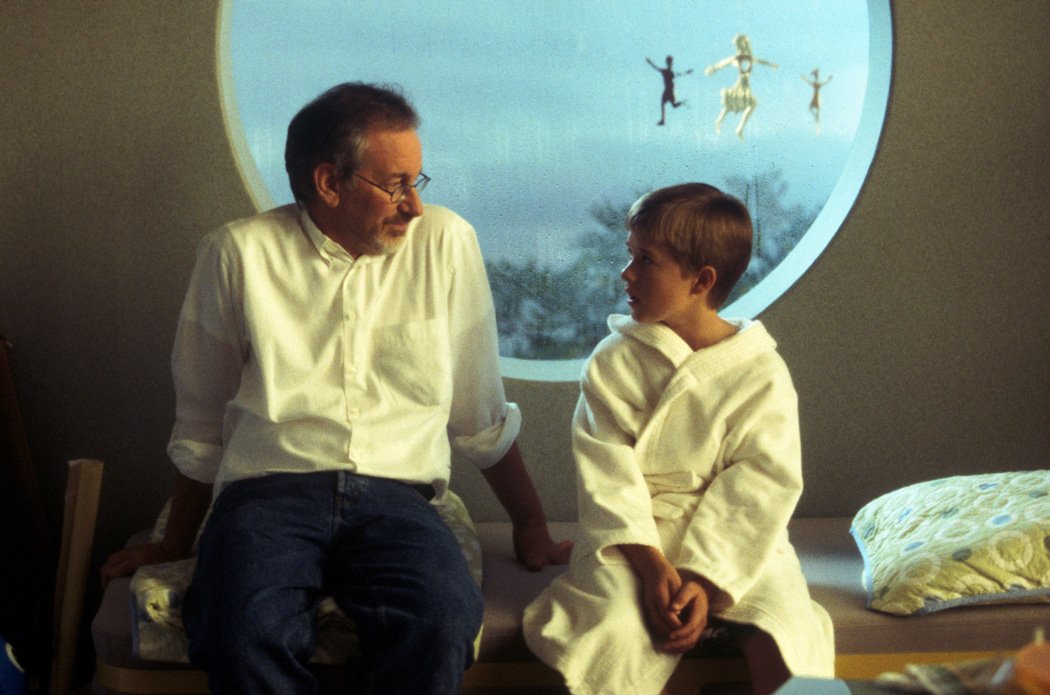

This film about a child robot's search for

love deals with subject matter that is

unique to famed director Steven

Spielberg--science fiction, children,

mind-blowing special effects--but the

dark and sometimes hopeless tone of A.I. may be a bit of a

departure for him.

Story

In the 21st century, life is not all

good on Earth. The polar ice

caps are melting, submerging many of the world's coastal

cities.

To help cope with the situation, artificial intelligences, or robots,

have been created, and are generally designed for specific

purposes--housework, babysitting

and even sex. A genius

professor (William Hurt) builds an 11-year-old child robot named

David (Haley Joel Osment) for a different purpose, a child android

that, once "imprinted" by his human parents, can actually feel

emotions. When

a couple (Frances O'Connor and Sam Robards),

despondent over the loss of their own son,

takes on the role of

David's "test" parents, they set in motion a personal

journey for

the young boy. Through a series of events, he is forced to seek

out his own humanity and attain the one thing he wants most in

the world--to be real

and to be truly loved.

Acting

OK,

if Spielberg had to sit down and find someone who could play

a child robot who just

wanted to be loved, his choice probably

wasn't that hard. Osment is just one of those

child actors who

breaks your heart the minute he comes on the screen. He did it in

The Sixth Sense and even in the melodramatic Pay It Forward. No

actor out there has the soulful face that he does. But his

performance in A.I. takes

the cake. Osment is almost eerily

perfect as David. Never once do you doubt he is artificial,

as he

watches with amazed curiosity, and sometimes horror, the world

around him. And never once so you forget that he wants

desperately to be real. There

are some nice supporting turns,

especially by Jude Law, playing the gigolo android who

helps

David in his quest, and by O'Connor as David's "mother." But it

was without question Osment's film.

Direction

Spielberg took over the project, based on the short story

Super-Toys Last All Summer

Long by science fiction author Brian

Aldiss, from the late Stanley Kubrick, who had

been trying to get

the film made for 20 years. And therein lies the film's main flaw:

it's not really a Spielberg special. It did have a lot of elements he

has made his own (he even expands on his Close Encounters

alien), but this film was

very dark, somewhat hopeless and pretty

slow. That's definitely not Spielberg's usual

direction for a movie,

especially one based on original material. Kubrick excelled at

bringing to life those slow, methodical story lines and didn't care if

an audience liked it or not, but Spielberg is used to creating

wide-eyed extravaganzas

and historical epics that capture their

audiences' hearts. Yes, Spielberg's war movies

are somber, but

that's because they are real--those events really happened. A.I. is

a different kind of Spielberg film, and some audiences may not be

ready for it.

from hollywood.com

Would you like to get science fiction perspective on Artificial

Intelligence? On the 28th of September, Steven Spielberg's new

movie "A.I", will be playing at cinemas across

Sweden.

The only thing you need to do to get two free tickets to the movie is

to tip us about a colleague

of yours who is in need of TiFiC.

Click here to tip us!

We are sorry to say that tickets only are

valid in Sweden.

About the Movie "A.I."

Sometime in the future of the 21st century, in

a time when the

Greenhouse Effect has melted the icecaps, submerging many of the

coastal cities in water, mankind

depends upon computers with

Artificial Intelligence to maintain our way of life. Man has also found

new friends

in A.I., in the form of robots that are used for a variety

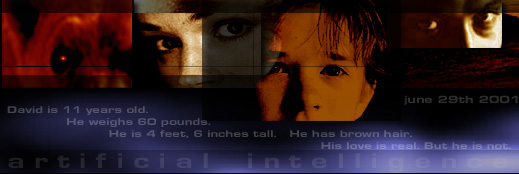

of functions. This story is about a boy robot (Haley Joel

Osment), and

the emotional journey he makes toward becoming... something

more.

Casting: Jude Law

& Haley Joel Osment

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Movie Profile

The Setup

Based on an unfinished project by

Stanley Kubrick, "A.I." imagines a

robot Pinocchio--David (Haley Joel

Osment)--who is abandoned by his

human mother and forced to make his

way

through a terrifying future world.

Jude Law is Gigolo Joe, a surrogate

sex machine who reluctantly befriends

the boy and guides him through some

hellish imagery that draws equally on

"Schindler's List" and "A Clockwork

Orange."

The Breakdown

The conjunction of two legendary

control freaks, Spielberg and Kubrick,

results in a wildly undisciplined feature

that seems to operate on pure id. All

the childhood trauma that Spielberg

carefully ironed out of his idyllic

suburban fantasies returns with a

vengeance: There are moments that

evoke the most anxiety-ridden Disney

classics ("Bambi" and the 1940

"Pinocchio") but Spielberg doesn't

offer Disney's consoling tenderness.

"A.I." is too personal and too reckless,

but that's a welcome change in a time

of bland and anonymous studio films.

Dave Kehr

Space Oddity

Spielberg and Kubrick had a weird little kid, and its name is A.I.

BY ROBERT WILONSKY

For almost two decades, Stanley Kubrick

wanted to

make a film based on Brian

Aldiss' 1969 short story "Super-Toys Last

All Summer Long," about a robot child

named David who wants only to be "real"

so Mummy and Daddy will love him. The

late director of 2001: A Space Odyssey

and A Clockwork Orange envisioned

"Super-Toys" as the frame upon which he

could hang his own reworking of

Pinocchio, and perhaps he also saw it as

an

extension of what he began in 2001:

David is HAL as a little boy, a machine

who aspires to consciousness and emotion

-- in other words, a machine that wants to

become like its creator. But Kubrick

found an even better director for his

project: friend Steven Spielberg, whom

"Super-Toys" would allow the chance to

revisit old themes and doll them up in the

fancy togs of a fellow mythmaker. He

could remake Close Encounters of the

Third Kind and E.T. in Kubrick's image.

He could commingle the childlike with the

clinical, the heartbreaking with the

heartless. Finally, Spielberg could make a

movie about children and aim it solely at

adults. (The movie is simply too slow, too

serious, even too sex-drenched to play to

kids.)

The results, then, are just as you would

expect: A.I. Artificial

Intelligence is

Kubrick as interpreted by Spielberg, which

means it's by turns

poignant and cold,

twisted and sweet, dreamy and drab,

effortless and overwrought.

In short, the

movie is a stunning, ambitious mess that

leaves you wondering

how much better it

might have been without Kubrick's

specter peering over

Spielberg's heavy

shoulders. But what else could it have

been? Theirs is hardly

a perfect marriage:

Kubrick's movies are chilly, existential

tone poems made

by a control freak who

loved movies but not necessarily the

people who paid

to watch them. His

perfectionism too often quashed whatever

passion sneaked

into his films -- they look

great but feel empty. Spielberg, especially

the

young man who made Close

Encounters and E.T. the

Extra-Terrestrial, revels

in innocence and

awe. Spielberg, the eternal optimist,

presents life as one

big happy ending:

We're going to be rescued, whether by

aliens or Roy Scheider

or Tom Hanks.

Kubrick, the curmudgeonly cynic, seemed

to believe we are all

doomed. One walks

out of his movies filled with hope only

because we hope

the world isn't as bad

off as he suggested.

A.I. attempts to reconcile

those disparate worldviews. The movie wants to

overwhelm you with sadness and despair, but it's too

frosty and

manipulative to elicit a single tear. Spielberg is credited with A.I.'s

screenplay -- it's the first time he's written and directed since Close

Encounters -- but the film

is faithful to both Aldiss' story and Ian Watson's

original screenplay, commissioned by Kubrick. Watching

it, you can't help

feeling that the director wanted to become Kubrick, which means this is

the first Spielberg movie that seems to have one hand on your chest,

keeping you at bay.

A.I. fleshes out, for lack of a better phrase, Aldiss' simple, heartbreaking

short story into a grand-scale

fairy tale -- Pinocchio as reimagined by the

visual-effects team at Industrial Light & Magic.

We learn at the film's

onset that the ice caps have melted and drowned Earth's biggest cities, and

in a distant, overpopulated future in which childbirth is regulated by the

proper authorities, humanoid robots have taken over our most menial

chores; they serve us, even pleasure

us, until they're discarded for better

models. Professor Hobby (William Hurt), A.I.'s Geppetto, proposes

to a

group of fellow robotic designers that they create a "robot who can love,"

and the result is little David (Haley Joel Osment), who is made of synthetic

flesh and computer circuitry.

Hobby is unprepared to answer the inevitable

Big Question: Can you get a human to love the robot back?

The response is found in the home of Monica and Henry Swinton (Frances

O'Connor and Sam Robards), whose flesh-and-blood son Martin (Jake

Thomas) suffers an illness that

requires that he be suspended in cryogenic

deep-freeze. His holding tank is in but one of myriad scenes

that look like

something lifted from 2001; the audience, like Martin, shivers in the sterile

setting. Henry, who works for Professor Hobby, envisions David as

Martin's replacement, but Monica

refuses to look at his unblinking,

expressionless face -- a machine bereft of true emotion but prone

to

disturbing outbursts of laughter. Monica finally warms to the cold little boy,

imprinting him with seven words that will forever bond mother and "child,"

and as she does

so, his face softens (Osment looks, on occasion, like Cary

Guffey, the child in Close Encounters who

longs to ride in the crystal

chandelier in the sky). The catch is that David can love only her, and

if

Monica ever decides she no longer wants David, he will have to be

destroyed.

But Monica and Henry will never love David as they do Martin, who one

day comes home from the hospital and begins treating his "brother" as if

he's nothing more

than the latest and greatest super-toy -- a better version

of their talking teddy bear. Martin taunts

David, constantly reminding him

of his artificiality; he's a "mecha" (a machine) in a world

of "orgas"

(organics). Martin gets Monica to read to them from Pinocchio: "David's

going to love it," Martin says with a cruel smirk. But the story gives David

hope: If he can find the Blue Fairy, he, like the puppet in the book, can

become a real boy.

The first third of A.I. feels so much like Kubrick it's as though the film had

been directed by a ghost. The Swintons' home, with its polished wood

floors and post-IKEA furnishings,

looks barely lived in. It's a quiet, lonely

place, and even composer John Williams, who's made millions

providing

Spielberg with orchestral bombast, stays hidden in the shadows with music

that's less a score than a whisper of strings. Up to this point, the movie

plays like small-scale

domestic drama -- the story of a rejected stepchild

wanting to love and be loved. But all that gives

way when Monica takes

David out in the forest to dump him, lest the rejected boy end up destroyed.

His screams pierce the soundtrack ("If I become a real boy, can I come

home?") as the landscape becomes suddenly desolate and threatening.

What follows next

is perhaps the most twisted Kubrick-Spielberg amalgam

imaginable: We're introduced to Gigolo Joe,

played by Jude Law behind a

thin veneer of makeup that turns him into a human-size sex doll -- Fred

Astaire on the dance floor, porn star John Holmes in the sack. Living in a

sleazed-out town, Joe comes across as something that could have been

cooked up by Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove

collaborator Terry Southern, a

man fond of his kink. "Once you have a lover robot," Joe

brags, "you'll

never go back." But Joe is nothing more than a plot device, the older

brother David never had. He belongs in a different movie -- a fun one.

When Joe finds himself

in bed with a dead girl, he's forced to go on the run

and winds up in a robot graveyard in which outdated,

gruesomely

half-destroyed models scavenge for parts. David and Joe are rounded up

for a Flesh Fair, where mechas are destroyed onstage for human

amusement. It's a horrific moment,

because it subverts an image from E.T.:

The moon literally rises out of the horizon and scoops up

the unsuspecting

androids, hauling them off to slaughter. It's BattleBots gone mad, a Klan

rally in which humans destroy their mechanical -- indeed, their superior --

counterparts.

Like 2001, A.I. suggests that artificial "humans" are better than the real

thing; if theirs is a synthetic love, at least their processors don't

manufacture synthetic hatred.

The humans are ogres, be they Monica

Swinton (who else but a hateful woman would dump a child in the

middle

of nowhere?) or Lord Johnson-Johnson (Brendan Gleeson), the

robot-hunter

who terrifies the Flesh Fair audience by insisting David is part

of a "plan to phase out God's

little children." But whatever point Spielberg

is trying to make about racism and fear of the

future is lost in the spectacle

and eventual sentimentality of the Flesh Fair sequence, which deteriorates

into proselytizing by way of the World Wrestling Federation. And because

we

see the struggle to define humanity through the eyes of David and Joe

and not their creators, the

battle between mechas and orgas becomes

simply too cartoonish to take seriously.

Joe finally leads David to a place where he might find the man who knows

the Blue Fairy: Rouge Town,

a dreamy Fuck City where denizens populate

A Clockwork Orange's milk bar, clubs are entered through

the parted

thighs of computer-generated women and Dr. Know provides answers to

scared little synthetic boys. And here, suddenly, the movie begins to fall

apart: Robin Williams,

as the voice of the Einstein look-alike Dr. Know,

conjures memories of his own Bicentennial Man, a

clumsy, sickly sweet

version of what's essentially the very same tale.

In the end, the film fails because Spielberg chickens out. Instead of a

Kubrick movie, he's remade

Close Encounters, only without the sense to

edit himself (even the music echoes Williams' use of "When

You Wish

Upon a Star"). A.I. comes to a very logical, if overpoweringly cheerless,

ending about 15 minutes before the final credits roll. But Spielberg plunges

forward, and the result

is frustrating and pointless. What had been a fairy

tale becomes daffy sci-fi tomfoolery; our emotions

are hung out to dry

along with some garish special effects that serve only to create distance

between David and the audience -- distance that didn't exist until that point.

It's as though

Spielberg has succumbed to the "ponderous seriousness" of

which Pauline Kael wrote in The

New Yorker when comparing Close

Encounters (which she loved) to 2001 (which she loathed). The

mythmaker who wants to explore just what makes us human (our desires

and drives, as it turns out,

not merely our emotions) succumbs to the

franchise-maker who wants to usher us out the door feeling

if not cheerful,

then at least satisfied. The ending -- which suggests that little boys want

nothing more than to sleep with their mothers -- is not enough to betray the

movie,

which is too engaging, too ambitious and too bizarre to dismiss, but it

suggests that Spielberg is

not quite ready to make grown-up sci-fi movies.

And he won't be until he figures out that happy endings

aren't always the

best endings.

More Reviews

tific Digital

newstimesla

movie search

|